Yom Kippur

Sermon by Rabbi Tobias Moss

2019/5780

Our TIPTY choir just sang Etz Chayim Hee. “It is a Tree of Life to those who hold fast to it; all who support it are happy.”

When I was a kid growing up in Tenafly, New Jersey, just outside of New York City, I too was part of a youth choir. At Temple Emeth, it was called Etz Chayim. Ever since then, those words have had a special place in my heart. It is a metaphor that seems to do justice to the otherwise impossible to summarize: the scope, span, and sustaining spirit of Judaism and Torah.

A tree reaches upward to the heavens, produces fruit for nourishment, and absorbs sunlight into vibrant green and multi-colored leaves. For me, this upward growth symbolizes the aspirations that Judaism lays out to me and how I might always achieve new spiritual heights.

Of course, a tree also digs deep roots which establish its history and give it power to withstand storms and winds. I know that I can forever explore my roots, the span of collected Jewish tradition, to find meaning and sustenance. So I love this metaphor, Etz Chayim—The Torah is a Tree of Life.

But these words were wounded, this byword was bloodied, this metaphor was marred, on October 27, 2018, with the tragic events at the Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha synagogue, in Squirrel Hill of Pittsburgh. This was the murder of eleven Jews, killed in the very act of holding fast to it, to Torah, the Tree of Life. In the Jewish vocabulary, there is a single word that captures our immediate reaction to such a moment: Eicha?!

How?

How come?

How is it so?

How do we proceed?

How is God involved?

How is God absent?

How was a 97-year-old woman named Rose a threat to anyone?

We have a whole book in the bible called Eicha, known in English as the Book of Lamentations. The scroll is recited on Tisha b’Av, a day that is fully dedicated to the mournfulness of lamentation. Yom Kippur is a more expansive, more awesome day, containing the full range of human emotion—from sadness to joy, from mourning to dancing. In my remarks, I will dig a little deeper into the former, into sadness, but I hope by the end of this sermon, that we also bring into view the joy and hopefulness that are just as much a part of this redemptive day.

A lament is something we’re not used to. It’s a crying out without a solution suggested, without consolation conferred. Rather, eicha is a question without an answer; an exclamation that doesn’t provide direction.

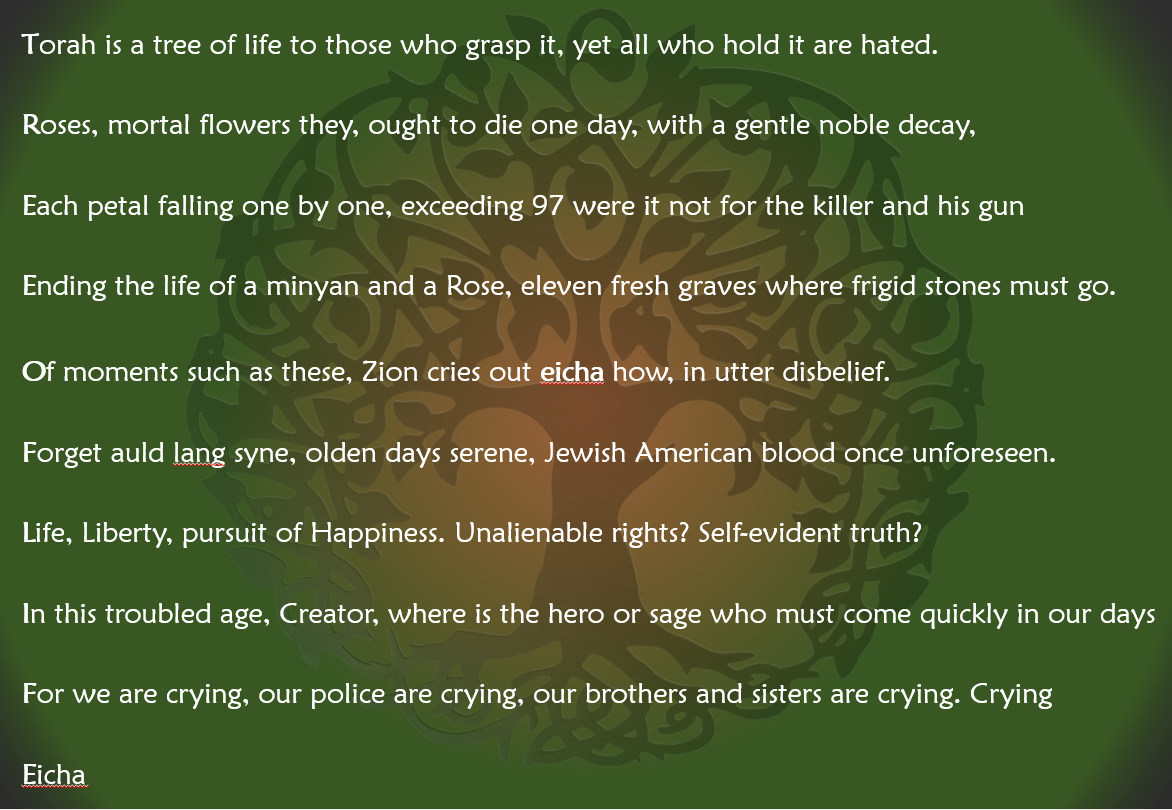

Would you please read with me the lament now projected above, which I wrote in the days following the Pittsburgh shooting.

It’s now almost a year since we all in our own way said eicha. Some cried it, some whispered, some wondered, some cursed.

It’s now almost a year of Kaddish for those 11. We can’t adequately memorialize them, though I know their home communities will.

It’s now almost a year since their synagogue was devastated. Did you know that their building remains shuttered, surrounded by a fence, and the congregants are meeting in other locations for these High Holy Days? We can’t purify their building from here.

It’s now almost a year since Etz Chayim Hee, this beloved metaphor, has been so tainted. Perhaps it is in my power, in our power, to help purify just that, just those words.

The Talmud records that in the ancient Temple ritual, a scarlet thread would become white if the Yom Kippur ritual was successful. How, then, can we make our bloodied Tree of Life return to its vibrant green? The rest of the verse gives us an answer. It is a tree of life to whom? To those who hold fast to it. We need to hold fast to our Torah.

In my moment of lament, when I wrote that poem, I asked for a hero or sage who could, perhaps like the ancient Temple Priest, take care of this all for me, for us. But a year later, we know that an act of devastation can only be answered by 1,000 acts of chesed, 1,000 acts of kindness. Our community, in Pittsburgh, in New York, and I know here as well, received and gave 1,000 acts of kindness after the tragedy. In Pittsburgh, Jew and non-Jew alike and even opposing sports teams, rallied around the slogan Stronger Than Hate. That together, America’s loving portion is much stronger than its hateful one.

No hero or sage can prove this alone. Rather, as our Torah portion reads, atem nitzavim, culchem hayom, you who stand here today, all of you, regardless of age or occupation, all have it in your power to observe these teachings. The teaching is very close to you, says Moses, it is already in your mouth and in your heart.

So when the shootings at Pittsburgh occurred, or Poway, San Diego, or outside of the Jewish community at Christchurch, Charleston, or elsewhere, we usually don’t need new instructions, we just need to act upon our teachings. These wicked people are often publishing manifestos, but we are not a manifesto type of people, making simple proclamations. Judaism is about show, don’t tell—not manifestos, but manifesting our commitments, our kindness. We grab hold of our Tree of Life, our Torah, in which study leads to action.

If our grasp was flimsy, we’d have stopped coming to synagogue a long time ago, though I know thousands of you came for the service following the shooting, and you are gathered here again today, holding fast.

If our grasp was flimsy, we wouldn’t check in on a sick neighbor or a mourning friend, but I’ve already witnessed how deeply this community looks out for each other, holds fast to each other.

If our grasp was flimsy, we’d bristle at the inconveniences of increased security, but holding fast means supporting the financial burden and enduring the psychological burden of this reality. We give gratitude to those who are keeping us safe.

Holding fast means making the extra effort to meet Judaism’s demands for justice throughout our society. As we heard Isaiah articulate in our Haftarah, “unlock the shackles of injustice, loosen the ropes of the oppressed, share bread with the hungry.”

Isaiah also tells us that holding fast means honoring and remembering Shabbat and calling it a delight. That’s not always easy for us, even for us clergy. I’ll share a simple story, which reminded me of what happens when we hold fast to Torah.

A few weeks after beginning here, my girlfriend visited for the first time. On her first Friday afternoon, within the whirlwind of work, we managed the mighty feat of having a meal cooked and the table set for two before returning to Temple for Shabbat services. After services, we walked back to my nearby home.

Two blocks from home, crossing the street, I did a double-take, thinking that I’d recognized someone. However, in my excitement to get back to “my Shabbat meal,” I ignored that double-take sensation, and shied away from an encounter. But a voice called out, “Tobias?!” And sure enough, it was a camp counselor I’d worked with at a Jewish summer camp in Colorado. The counselor had been an acquaintance, but not more than that. We stopped to chat.

Like me, she’d just moved to Minneapolis. We marveled at the coincidence, but truthfully, honestly, my attention wasn’t with her. My attention was going towards my house two blocks away, to an intimate meal, an overdue catch-up, and time away from the new pressures of this public rabbinical role. But then that Torah-infused conscience of mine started piping up, like Pinocchio with a Jewish Jiminy Cricket inside. Or as Moses puts it, “the instruction is already upon our hearts and our lips.” So Mitzvot, commandments, and Jewish values flew across my brain: Jewish hospitality, welcoming someone new to town, inviting someone for Shabbat dinner, making Shabbat a delight. So I grabbed hold of that little piece of Torah, and invited her to join us for dinner. We re-set the table for three.

It was a small act, but most of life, thankfully, is responding to small moments, small opportunities. I didn’t solve a great ethical dilemma. I didn’t give some great sum of money to tzedakah. But now that Shabbat guest is no longer just an acquaintance, but one of my first friends in the Cities. She’s been back for another meal. She came here for Erev Rosh HaShanah services. Grabbing hold of just a little bit of Torah ultimately brought more joy to my world; I think to hers as well.

The rabbis say mitzvah gorreret mitzvah, a mitzvah leads to another mitzvah. Acts of lovingkindness self-propagate. Joy ripples through a society.

Now earlier I promised that Yom Kippur is known to tradition as a joyous day. The Talmudic rabbis say that there’s simply a joy inherent with repentance and finding forgiveness. An earlier sage provides a more specific illustration. Rabbi Shimon Ben Gamliel records the following tradition: There were no days of joy in Israel greater than Tu B’av (Jewish Valentine’s Day, in short) and Yom Kippur. On these days, anyone seeking a mate would dress in white gowns. All the gowns had to be borrowed, so that no one would know who was rich, who was poor, who was from royal or priestly descent, and who was a common Israelite. These white-wearing singles would go dance in the vineyards and meet their suitors. Who would think that the day of reckoning could have such romance? That the earliest JDate occurred on Judgement day?

Now, we do things a little bit different at Temple. Now it’s just us clergy that wear these white robes, and the white-clad Torah scrolls. I promise, we’re not about to dance for you; that holiday is in two weeks.

But on this day, joy still comes into focus. After the Kol Nidre awe of last night, after our introspection of this morning, after the healing and memorial services this afternoon, during Yom Kippur’s climactic conclusion, during Ne’ilah, we’ll bring up all the new babies of the congregation this year. They are our dancing joyful reminder on this Yom Kippur.

Rabbi Jeffrey Meyer, the Tree of Life synagogue rabbi who many of us saw on the news, asks what is the most important day of the Jewish year? His answer is the day after Yom Kippur. The day when we begin to choose, will our grasp on Torah be flimsy or held fast? That seems to me to be why Yom Kippur was once a day for finding your mate, and now is a day to celebrate babies and the next generation. We are celebrating tomorrow and all the coming opportunities, big and small, all the opportunities to hold fast to the Tree of Life. All its supporters bring happiness into the world. Shanah Tovah.