Sermons

Holiday and Hebrew Year

Yom Kippur

Sermon by Rabbi Sim Glaser

2019/5780

The Torah portion read this morning by our children is said to have been written by Moses, the greatest prophet of Israel.

The action takes place at Mt. Sinai where the covenant is made between God and the people Israel. This covenant is binding on everyone, not just the powerful elite, not only the head honchos of the tribes, but every woman, man, and child. An agreement for all the generations to come, right down to the present day.

Also mentioned in the portion is that there is nothing God is asking of us that is impossible to do or understand. It should all make perfect sense. With this guidance, there is nothing we cannot do in the work of perfecting this world.

The Torah portion is traditionally followed by the Haftarah, which is a section taken from the Prophetic books. When most people think of prophets, they think of predictors of the future. But in Israelite tradition, the prophet is one who awakens their community to the harsh realities of the present day and our overall behavior.

Essentially, the three roles of the Israelite prophet are:

When the people have misbehaved the Prophet says: You have messed up and you’re gonna suffer!

When the suffering begins the Prophet says: You see, I told you so!

And finally, a message very important to this holiday of Yom Kippur:God is ready and willing to still deal kindly with you if and when you mend your ways.

There have been many kinds of prophetic types in Israelite history. Some of them are famous old friends.

Abraham, who brought the message of a one-and-only God who was an ethical commanding presence to the world. The rabbis teach that when he had his “aha” moment as a young man, he had to smash a shop full of idols to break with the past. Abraham was ridiculed for talking to and even bargaining with an invisible God.

Then there was Moses, who claimed no monopoly on the craft. No, he believed every single one of us is equipped with the bandwidth for prophecy. Moses was assailed by rebellious Israelites for thinking he was a big shot. He wound up having a desert meltdown.

Jonah, whose book we read this very Yom Kippur afternoon, gets the Divine Tweet and responds by running as far away from God as possible, because he didn’t believe in giving people second chances!

Jeremiah, who foretold the destruction of Jerusalem by fire, and who was known as the weeping prophet, admonishes the people and gets thrown into a pit.

And let’s not forget Noah, who receives the heavenly call to action, builds a boat and sails away without as much as a word of advice for his fellow earthly inhabitants. In the hundred years it took him to build the ark, Noah was teased and maligned every step of the way for his doomsday approach.

Three thousand years later, a young girl from Sweden gets on a rather different kind of boat, travelling via sun-powered watercraft across the Atlantic, and tells the world that we are the flood, and we are the ark. “I want you to act as if your house is on fire,” she says, “because it is! You say you love your children above all else, yet you are stealing their future in front of their eyes.”

If those words sound familiar to you, it is because either you saw Greta Thunberg addressing the United Nations, or you heard her prophetic call as the recitation of the Haftarah just moments ago.

In almost every instant, the prophet is mocked, challenged, and their warnings are diminished as nonsense. But Greta has the added disadvantage of being a teenager and not taken seriously by the generation that has allowed our world to be in the precarious state it is in.

Indeed, none of the prophets of Israel were children. But each of them experienced deep personal pain over what had befallen their people. And perhaps this is why the modern prophet needs to be a child. Because maybe the rest of us just aren’t hurting enough about a calamity that won’t reach its full strength until after we have departed this world!

I have had control of a public microphone for 31 years as a professional clergyman, and have too rarely addressed what now appears to be the issue of our lives because I thought it might ruffle political feathers.

So I consider myself complicit. But if I am unable to hurt enough about it to be prophetic, then I am going to listen to the next generation tell me what needs to be done. We may not have been so great leading out in front, but our children should know that we have their backs! We should support them, or, at the very least, get out of their way!

This year, during the hottest July ever recorded in human history, Iceland memorialized its first ever loss of a glacier to climate change. At a funeral for the Okjökull glacier, the Icelandic Prime Minister and the former UN Human Rights Commissioner dedicated a plaque at the former site of the glacier which bore the inscription “A letter to the future.” And it read simply:“In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

I don’t want you to feel cheated out of your Haftarah today. By all means, read the Isaiah passage if you like. It is a beautiful piece of prophecy that calls us to see our fast as representative of hungry homeless people in our midst. It is as relevant today as it was 3,000 years ago when it was penned.

If it makes you feel any better, the Torah portion we read isn’t the original Yom Kippur passage either. Though we’ve become quite used to it, Reform Judaism exchanged an old parsha about an ancient atonement ritual sacrifice to a more effective Yom Tov message – that the solution to our problems is not somewhere out in heaven and unreachable by us!

This year we replaced Isaiah with a young modern prophet who is bringing the world a message it somehow doesn’t want to hear. And like the prophets, Greta has been called everything you could imagine.

Journalists and climate deniers and political figures all the way up to the top are maligning Greta and her prophecy, ridiculing her, calling her a petulant teenager, and diagnosing her mental capacity much in the way they badmouthed and critiqued the brave young Parkland survivors when they spoke out, finding every possible reason to reject the validity of their claims: that we have let the next generation down.

One critic labelled her a propaganda tool for leftist adults pushing their agenda. Others said, don’t listen to teenagers. They only repeat back what their elders have told them.

Really? Are you kidding? Have any of these people ever met a 16-year-old that does what grown-ups tell them to do?!

Nevertheless, millions of children worldwide took to the streets in response to Greta’s prophecy. They are sounding a shofar blast quite unlike any my generation has been able to muster. They are letting us know that their future is dependent on our present.

You know that Judaism believes in the power of our children. Perhaps our greatest display of confidence in their youthful character and ability to lead is that at the age of 13 we trot them out to read from the Torah and lead the congregation in worship, where they deliver a speech to us telling us what is important to them. They become part of our minyan – we not only count them, we count on them! Right here today we are counting on them to lead us in worship on this, the holiest day of the year!

So here we are in 5780, at the start of a new decade, and we are still involved in a covenant. The earliest biblical covenant was that of the rainbow and God’s promise never to destroy the earth. As one modern author puts it, a rainbow is a rope: it can be thrown to a drowning person, or it can be tied into a noose. No one who isn’t us is going to destroy Earth, and no one who isn’t us is going to save it. The most hopeless conditions can inspire the most hopeful actions. We are the flood, and we are the ark.

I think Moses was right when he said that each of us has the potential for receiving prophecy. We enact prophecy every time we name our children. We give them names like Gabriel, Gavriel – God is my strength, and Nathaniel – Natan-El – a gift of God, or Ezra – helper; Hannah – merciful.

We even give them the actual names of the Prophets, like Yonah and Noah and Yoel.

We bestow names that reveal our deep love of the physical world like Ilan – tree, Aviva Springtime; Devorah – honeybee; Yael – mountain goat. Greta – a Swedish form of Margaret (my granddaughter’s name), the Hebrew equivalent is Margalit – meaning Pearl… as in something choice… or precious… or as in: pearls of wisdom.

Every child’s name is an investment in the future. And now these children, with these prophetic names, are asking us to reconsider the world we are leaving them.

A beautiful Midrash we often employ at those naming ceremonies tells of God talking to the Israelite nation, asking, who will guarantee the future? The Israelites quickly respond that of course our great ancestors will guarantee the future! To which God says, “Oh that was so yesterday. Who will guarantee the future?” The people answer, saying the great Prophets of Israel will guarantee the future. God says that even the prophets of old are insufficient guarantors. Finally the Israelites get it right and say: “Our children will guarantee the future!”

“Now you’re talking,” says God. “The children are indeed fine guarantors. It is because of them that I give you the Torah.”

And it will be because of our children that we all will merit, God willing, an inhabitable world.

Yom Kippur

Sermon by Rabbi Tobias Moss

2019/5780

Our TIPTY choir just sang Etz Chayim Hee. “It is a Tree of Life to those who hold fast to it; all who support it are happy.”

When I was a kid growing up in Tenafly, New Jersey, just outside of New York City, I too was part of a youth choir. At Temple Emeth, it was called Etz Chayim. Ever since then, those words have had a special place in my heart. It is a metaphor that seems to do justice to the otherwise impossible to summarize: the scope, span, and sustaining spirit of Judaism and Torah.

A tree reaches upward to the heavens, produces fruit for nourishment, and absorbs sunlight into vibrant green and multi-colored leaves. For me, this upward growth symbolizes the aspirations that Judaism lays out to me and how I might always achieve new spiritual heights.

Of course, a tree also digs deep roots which establish its history and give it power to withstand storms and winds. I know that I can forever explore my roots, the span of collected Jewish tradition, to find meaning and sustenance. So I love this metaphor, Etz Chayim—The Torah is a Tree of Life.

But these words were wounded, this byword was bloodied, this metaphor was marred, on October 27, 2018, with the tragic events at the Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha synagogue, in Squirrel Hill of Pittsburgh. This was the murder of eleven Jews, killed in the very act of holding fast to it, to Torah, the Tree of Life. In the Jewish vocabulary, there is a single word that captures our immediate reaction to such a moment: Eicha?!

How?

How come?

How is it so?

How do we proceed?

How is God involved?

How is God absent?

How was a 97-year-old woman named Rose a threat to anyone?

We have a whole book in the bible called Eicha, known in English as the Book of Lamentations. The scroll is recited on Tisha b’Av, a day that is fully dedicated to the mournfulness of lamentation. Yom Kippur is a more expansive, more awesome day, containing the full range of human emotion—from sadness to joy, from mourning to dancing. In my remarks, I will dig a little deeper into the former, into sadness, but I hope by the end of this sermon, that we also bring into view the joy and hopefulness that are just as much a part of this redemptive day.

A lament is something we’re not used to. It’s a crying out without a solution suggested, without consolation conferred. Rather, eicha is a question without an answer; an exclamation that doesn’t provide direction.

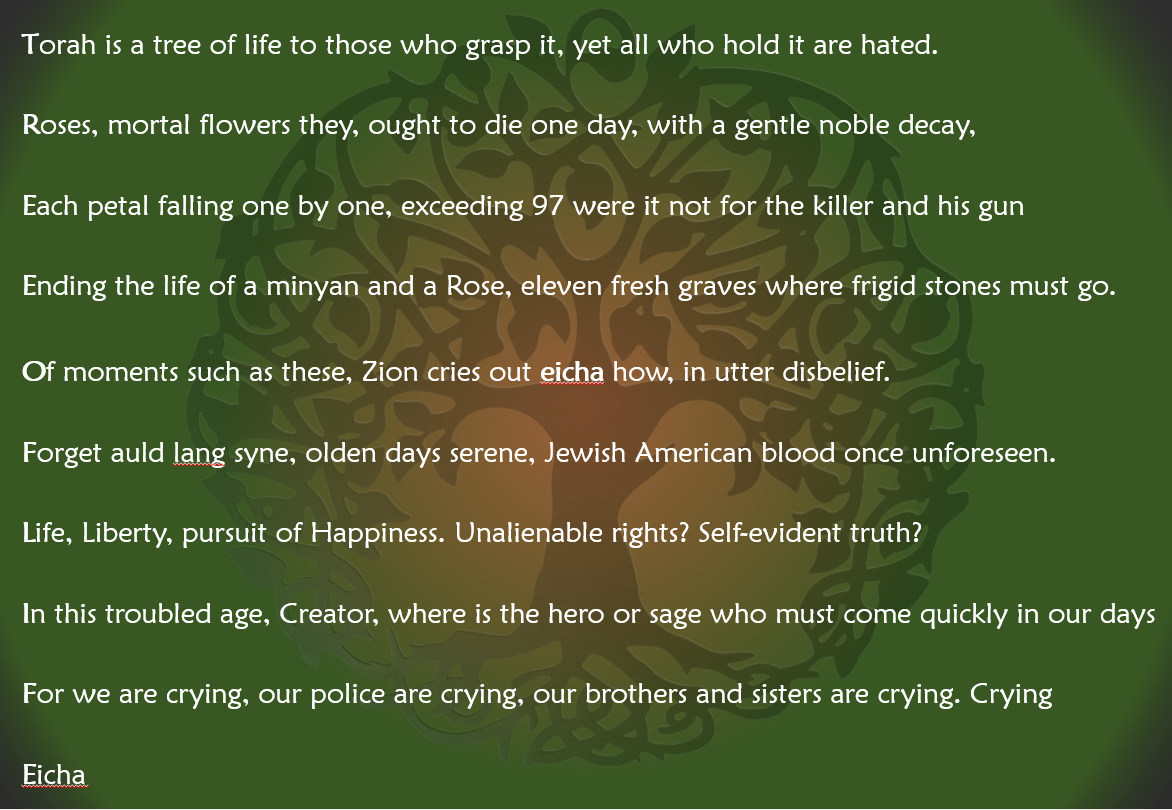

Would you please read with me the lament now projected above, which I wrote in the days following the Pittsburgh shooting.

It’s now almost a year since we all in our own way said eicha. Some cried it, some whispered, some wondered, some cursed.

It’s now almost a year of Kaddish for those 11. We can’t adequately memorialize them, though I know their home communities will.

It’s now almost a year since their synagogue was devastated. Did you know that their building remains shuttered, surrounded by a fence, and the congregants are meeting in other locations for these High Holy Days? We can’t purify their building from here.

It’s now almost a year since Etz Chayim Hee, this beloved metaphor, has been so tainted. Perhaps it is in my power, in our power, to help purify just that, just those words.

The Talmud records that in the ancient Temple ritual, a scarlet thread would become white if the Yom Kippur ritual was successful. How, then, can we make our bloodied Tree of Life return to its vibrant green? The rest of the verse gives us an answer. It is a tree of life to whom? To those who hold fast to it. We need to hold fast to our Torah.

In my moment of lament, when I wrote that poem, I asked for a hero or sage who could, perhaps like the ancient Temple Priest, take care of this all for me, for us. But a year later, we know that an act of devastation can only be answered by 1,000 acts of chesed, 1,000 acts of kindness. Our community, in Pittsburgh, in New York, and I know here as well, received and gave 1,000 acts of kindness after the tragedy. In Pittsburgh, Jew and non-Jew alike and even opposing sports teams, rallied around the slogan Stronger Than Hate. That together, America’s loving portion is much stronger than its hateful one.

No hero or sage can prove this alone. Rather, as our Torah portion reads, atem nitzavim, culchem hayom, you who stand here today, all of you, regardless of age or occupation, all have it in your power to observe these teachings. The teaching is very close to you, says Moses, it is already in your mouth and in your heart.

So when the shootings at Pittsburgh occurred, or Poway, San Diego, or outside of the Jewish community at Christchurch, Charleston, or elsewhere, we usually don’t need new instructions, we just need to act upon our teachings. These wicked people are often publishing manifestos, but we are not a manifesto type of people, making simple proclamations. Judaism is about show, don’t tell—not manifestos, but manifesting our commitments, our kindness. We grab hold of our Tree of Life, our Torah, in which study leads to action.

If our grasp was flimsy, we’d have stopped coming to synagogue a long time ago, though I know thousands of you came for the service following the shooting, and you are gathered here again today, holding fast.

If our grasp was flimsy, we wouldn’t check in on a sick neighbor or a mourning friend, but I’ve already witnessed how deeply this community looks out for each other, holds fast to each other.

If our grasp was flimsy, we’d bristle at the inconveniences of increased security, but holding fast means supporting the financial burden and enduring the psychological burden of this reality. We give gratitude to those who are keeping us safe.

Holding fast means making the extra effort to meet Judaism’s demands for justice throughout our society. As we heard Isaiah articulate in our Haftarah, “unlock the shackles of injustice, loosen the ropes of the oppressed, share bread with the hungry.”

Isaiah also tells us that holding fast means honoring and remembering Shabbat and calling it a delight. That’s not always easy for us, even for us clergy. I’ll share a simple story, which reminded me of what happens when we hold fast to Torah.

A few weeks after beginning here, my girlfriend visited for the first time. On her first Friday afternoon, within the whirlwind of work, we managed the mighty feat of having a meal cooked and the table set for two before returning to Temple for Shabbat services. After services, we walked back to my nearby home.

Two blocks from home, crossing the street, I did a double-take, thinking that I’d recognized someone. However, in my excitement to get back to “my Shabbat meal,” I ignored that double-take sensation, and shied away from an encounter. But a voice called out, “Tobias?!” And sure enough, it was a camp counselor I’d worked with at a Jewish summer camp in Colorado. The counselor had been an acquaintance, but not more than that. We stopped to chat.

Like me, she’d just moved to Minneapolis. We marveled at the coincidence, but truthfully, honestly, my attention wasn’t with her. My attention was going towards my house two blocks away, to an intimate meal, an overdue catch-up, and time away from the new pressures of this public rabbinical role. But then that Torah-infused conscience of mine started piping up, like Pinocchio with a Jewish Jiminy Cricket inside. Or as Moses puts it, “the instruction is already upon our hearts and our lips.” So Mitzvot, commandments, and Jewish values flew across my brain: Jewish hospitality, welcoming someone new to town, inviting someone for Shabbat dinner, making Shabbat a delight. So I grabbed hold of that little piece of Torah, and invited her to join us for dinner. We re-set the table for three.

It was a small act, but most of life, thankfully, is responding to small moments, small opportunities. I didn’t solve a great ethical dilemma. I didn’t give some great sum of money to tzedakah. But now that Shabbat guest is no longer just an acquaintance, but one of my first friends in the Cities. She’s been back for another meal. She came here for Erev Rosh HaShanah services. Grabbing hold of just a little bit of Torah ultimately brought more joy to my world; I think to hers as well.

The rabbis say mitzvah gorreret mitzvah, a mitzvah leads to another mitzvah. Acts of lovingkindness self-propagate. Joy ripples through a society.

Now earlier I promised that Yom Kippur is known to tradition as a joyous day. The Talmudic rabbis say that there’s simply a joy inherent with repentance and finding forgiveness. An earlier sage provides a more specific illustration. Rabbi Shimon Ben Gamliel records the following tradition: There were no days of joy in Israel greater than Tu B’av (Jewish Valentine’s Day, in short) and Yom Kippur. On these days, anyone seeking a mate would dress in white gowns. All the gowns had to be borrowed, so that no one would know who was rich, who was poor, who was from royal or priestly descent, and who was a common Israelite. These white-wearing singles would go dance in the vineyards and meet their suitors. Who would think that the day of reckoning could have such romance? That the earliest JDate occurred on Judgement day?

Now, we do things a little bit different at Temple. Now it’s just us clergy that wear these white robes, and the white-clad Torah scrolls. I promise, we’re not about to dance for you; that holiday is in two weeks.

But on this day, joy still comes into focus. After the Kol Nidre awe of last night, after our introspection of this morning, after the healing and memorial services this afternoon, during Yom Kippur’s climactic conclusion, during Ne’ilah, we’ll bring up all the new babies of the congregation this year. They are our dancing joyful reminder on this Yom Kippur.

Rabbi Jeffrey Meyer, the Tree of Life synagogue rabbi who many of us saw on the news, asks what is the most important day of the Jewish year? His answer is the day after Yom Kippur. The day when we begin to choose, will our grasp on Torah be flimsy or held fast? That seems to me to be why Yom Kippur was once a day for finding your mate, and now is a day to celebrate babies and the next generation. We are celebrating tomorrow and all the coming opportunities, big and small, all the opportunities to hold fast to the Tree of Life. All its supporters bring happiness into the world. Shanah Tovah.

Yom Kippur

Sermon by Rabbi Jennifer Hartman

2019/5780

It is never quite clear what brings us into the sanctuary on Yom Kippur. For some of us, it is our commitment to Jewish observance; for others it is our commitment to family; for still others it is about tradition. But, underlying all of this, there is a feeling in our kishkes about the true awesomeness of this day. It is the imagery of the gates closing and our fate being decided that pulls many of us in. Even those of us who do not believe in God, or are not so sure about this whole book of life and death thing, still decide to hedge our bets and show up. We walk into the synagogue, we are moved by the prayers chanted by the cantor, we are inspired by the power of this day.

Yom Kippur forces us to face our mortality, and allows us to enter the year renewed. The symbols of Yom Kippur, from fasting to wearing white, to staring into an empty ark during “Kol Nidre,” simulate our death in order to shock us into fully living our lives every day. It gives us time to engage in t’shuva, repentance, and cheshbon hanefesh, the cleansing of our souls. It allows us to evaluate our lives and enables us to confront the New Year with strength, resolve, and excited anticipation.

Rabbi Alan Lew writes a stunning description of Yom Kippur in his book This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation. He explains: “On Rosh HaShanah the Book of Life and the Book of Death are opened once again, and our name is written in one of them. But we don’t know which one. Then we come to Yom Kippur and for the next twenty-four hours we rehearse our own death. We wear a shroud and, like a dead person, we neither eat nor drink. We summon the desperate strength of life’s last moments . . . We utter a variation of the confessional that we will say on our deathbeds. Our fists beat against the wall of our hearts relentlessly, until we are brokenhearted and confess to our great crime. We are human beings, guilty of every crime imaginable . . . Then a chill grips us. The gate between heaven and earth suddenly begins to close . . . This is our last chance. Then the gate clangs shut and the great horn sounds one last time.”

The imagery described above shakes us to our core. It is meant to wake us up and ask us to take ourselves and our actions as seriously as they deserve. This is emphasized with the prayers of our machzor, those like the Unetaneh Tokef, whose words spell out all of the possible ways we could die. The prayer begins: “Let us proclaim the holiness of this day for it is awe-inspiring and fearsome” and continues by asking, “Who shall live and who shall die? Who by fire and who by water?” This could easily paralyze us. Yet, in our tradition’s brilliance, it does not allow us to remain in the fear. Instead, it lifts us up and out of it by giving us a way to counter God’s judgement. Embedded in the Unetaneh Tokef are directions for taking control of our future, the way that we can influence the judge’s verdict. Through repentance, prayer, and charity, we can avert God’s severe decree.

Every year, we come into this sanctuary to enact our own death and be restored to life with a new sense of hope and resolve. We come together for the courage to let go of our fears and our doubts. We come together to answer the call of Nitzavim, the Torah portion Cantor Kobilinsky just chanted so beautifully.

הַעִדֹתִי בָכֶם הַיּוֹם, אֶת-הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת-הָאָרֶץ--הַחַיִּים וְהַמָּוֶת נָתַתִּי לְפָנֶיךָ, הַבְּרָכָה וְהַקְּלָלָה.

“I call heaven and earth to witness this today: I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse — therefore choose life!”

Hope. The imagery is severe, but it never leaves us without hope, which can be one of the hardest emotions to conjure. Renowned writer and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel teaches that just as a person cannot live without dreams, he or she cannot live without hope: “It is hope that gives us the strength to fulfill our dreams; it is hope that allows us to take the next step forward even when all seems lost.” For Wiesel, it was hope that allowed him to survive the camps. He explains, “After experiencing the concentration camps, [he] had been a part of a universe where God, betrayed by humanity, covered God’s face in order not to see. Humanity, jewel of creation, succeeded in building an inverted Tower of Babel, reaching not toward heaven but toward an anti-heaven, there to create a parallel society, a new ‘creation’ with its own princes and gods, laws and principles, jailers and prisoners.” Even having experienced all of this, Wiesel still understood the integral role that hope plays in not only the Jewish story, but also that of humanity.

Hope, survival, continuing on, is ingrained in our souls even if it is not always accessible.Hope is the reason children are born in displaced person camps or refugee camps; it is the reason that people get on boats that very well might sink or walk for miles and miles with only the clothes on their backs for the potential to enter a new land. It is what motivates each of us to work to try to make the world better for the next generation – even when it is an uphill battle. Yes, hope is a part of the very fabric of being human, yet it often feels that we have lost the ability, or maybe the courage, to hope.

Therefore, maybe we can find inspiration in the stories of those who find hope in the face of uncertainty. A dear friend and mentor recently recommended that I read an essay by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi entitled “Toward a History of Jewish Hope,” in which the author reframes our past of exile and expulsion from one of sorrow and pain into one of resilience, confidence, and possibility. Yerushalmi understands that since the Holocaust, the Jewish community has organized its collective lives around that era of destruction and death. He embarks on the journey of finding hope in our collective history in order to reorient future generations from fear of extinction to hope for prosperity. He argues that “Memory of the past is incomplete without its natural complement – hope for the future.” And, he continues, from ancient times through today, this hope can be seen in our people’s willingness to resettle.

The urge to change our place in order to change our luck dates back to the Torah. There is a Hebrew saying that means just this – meshane makom, meshane mazal. From the birth of the Israelite nation where God tells Abraham and Sarah “Lech lecha – leave your homeland and go to a land that I will show you,” to the Israeli covert operation Solomon that brought Ethiopian Jews to Israel in the early 1990s: as a people, we have an expansive history of leaving one land with the faith and hope that we will be able to live rich Jewish lives in the next.

So many of us have these stories of parents or grandparents or even ourselves, picking up and moving to a foreign country. For some of us the reason is obvious – either we live or we die. The future may be unsure, but the alternative is dire. For others, the reasoning is less concrete. We want a better life, we think the new place will have more opportunities for us, we need a change!We engage in our own personal Yom Kippur; we have a reckoning with ourselves, our families, we see what life will be like if we continue on the path we are on, and we choose hope in the future. This hope, in the face of adversity, coupled with courage and ultimately action, can be transformative.

Two years ago I was selected as a member of a religious leadership cohort called the Collegeville Multi-faith Fellows Program. This program brought together 11 religious leaders from the Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim communities several times over a two-year period to meet with leaders from various facets of society including government, business, education, criminal justice, and health care. The purpose of this cohort was two-fold: (1) to gain insights into the unique opportunities and challenges Minnesota residents are expected to encounter in the decades ahead from a worker shortage to a growing senior population; and (2) to establish interreligious relationships with like-minded leaders so we can partner in creating solutions. Rabbi Barry Cytron and Dr. Marty Stortz of Augsburg University co-directed the program.

As this cohort met, debated, and unpacked the insights and predictions of our speakers, I was struck by Marty’s quiet optimism about the future. About halfway through the fellowship, I came to understand how deeply this optimism had been tested. I learned that only a few years into her marriage to Professor William Spohn, he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of brain cancer. Through his illness and untimely death, Marty learned much about hope and the role that it plays in sustaining people during their darkest moments. In her writings, she reframes what it means, and how we come by hope. As Marty and her husband William faced the cancer, the treatments, the side effects, and ultimately his death, they found that they never lost hope – they just changed what they hoped for.

Marty and William were deeply religious and spiritual people, yet it was not beyond them to become angry at God. To shake their fists and scream and yell. In truth, they may have done this in the privacy of their own home, during their nightly recaps, as they learned their physical time together was coming to an end. But they also felt God’s presence strongly. They felt God was paying attention to them through the love of their friends and family.

In one particular article, Marty admits that she could not always imagine what to hope for, but a deep and abiding hope held her and William. All they had to do was fall into it, like a trapeze artist falling into a net. The trapeze star had missed the catch, but she dared everything, because she knew the net was there. Neither of them had fallen off God’s radar screen, for they were both surrounded by the love of family and friends. So she was hopeful—devastated, no doubt, but also hopeful.

For Marty, this was the kind of hope that did not look forward to possible outcomes, but reached back to what was real. And what was real? For them, it was the sturdiness of the relationships with family and friends, the solidity of work, the daily graces that swarmed them. It was the family who came for a visit and knew not to stay too long, the friends who brought food to nourish them. It was colleagues who allowed them respite from the ups and downs of treatment. This is what sustained them during the never-ending tests and appointments. This is also what gave Marty the hope, and the courage, to leave California when a wonderful opportunity opened up for her here at Augsburg.

Hope is at the center of the story of Aaron Rapport and his wife Joyce. Aaron graduated from the Blake School in 1999 and went on to receive a graduate degree at Northwestern before completing his doctoral program at the University of Minnesota. It was here in Minnesota that he met his wife. They both became professors, first teaching in Atlanta and then in Cambridge. As the two built their careers and their lives together, they also fought cancer together.

Joyce was diagnosed in 2010 and Aaron in 2015. Neither allowed their diagnosis to stop them. Joyce became the assistant director of the newly-established University of Cambridge Office of Scholarly Communication, eventually working on special projects for the department in order to encourage researchers to share their data.Aaron was a Fellow of Corpus Christi College and lecturer in the Department of Politics and International Studies at Cambridge. He had already established a considerable international reputation, particularly following the publication of his book Waging War, Planning Peace in 2015.

It was their hope for the future that allowed them to move their lives to Cambridge, to build their careers, to continue to teach and work until the very end. Hope is what kept their marriage strong, even as they both went through their respective chemotherapies. For those who knew them, they will always be thought of as a perfectly-matched pair who never shied from sharing their philosophy of life with their students. During one conversation, Aaron’s student opined that “you only live once.” Aaron’s response? "You only die once; you live every day."Both Aaron and Joyce passed away this summer.

After sounding the alarm, the wake-up call that summons us on Yom Kippur, Rabbi Alan Lew looks further into our tradition and teaches us that at its core, Yom Kippur is a day of healing, a day of repair, a day that recognizes our fundamental brokenness and provides us with a remedy. Yom Kippur, in other words, is a day of hope, hope to carry us into and through the New Year. It is a day devoted to strengthening the hope we have and allowing us to renew hope that may be waning. It is a day when we pray not only to be sealed in the book of life, but also to have the courage for a life lived with hope. Ken Yahi Ratzon, May this be God’s will.

Erev Yom Kippur/Kol Nidre

Sermon by Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman

2019/5780

There’s a story about the Kotzker Rebbe. The Rebbe decides that he is going to spend Shabbat with a friend, and so he puts on regular street clothes for Shabbat. And because he is speaking at a nearby town, giving a very famous lecture, he has to board the plane as Shabbat is completed in order to arrive late at night. He doesn’t change his clothes into the clothes that a Rebbe wears.

He gets on the train and there are three students who are going to hear his lecture, but they don’t recognize the Rebbe. They begin to make fun of this old man who is feeble and moving too slowly. They laugh at him, they joke at his expense, and they even try to trip him as he walks slowly down the train car. They arrive at the town and they are excited to hear the Rebbe! And then, the reality hits them. Before the train has arrived, the Rebbe has changed his clothes and begins to exit to a big fanfare of the community waiting for him, and they realize that they have been making fun of the Rebbe himself. Shocked, they begin apologizing profusely. “Oh my goodness, Rebbe, we didn’t mean it. We feel so guilty! We are so sorry; we apologize.” The Rebbe lets this go on for some time until he finally turns to these three students and says, “You have apologized to the Rebbe, but now I want you to apologize to the old man on the train.”

Failed apologies seem to be all around us, don’t they? We have a lot of people who have done wrong in the world; hurt people. Really hurt people. And either have failed with an apology or haven’t apologized at all. Sackler family and the opioid epidemic, not taking responsibility . . . Madoff . . . We have Harvey Weinstein. We have Cosby. We have Louis C. K. . . . Over and over and over again, there are people in our midst who do not apologize, and I believe it puts our world out of balance and desperately in trouble. It is truly this idea that Aaron Lazare talks about, who was the chancellor of the University of Massachusetts medical school and has spent his entire career studying apologies. He wrote a book on apology. He says that you can apologize too soon, but actually, you can never apologize too late, meaning you should always apologize no matter how long ago the offense was. But too soon is a reality, Lazare says, because often when one apologizes too soon it’s to manipulate the situation. It’s to keep the anger of those offended at bay. And most of all, the offender has not done the work, the important internal reckoning, to understand what they have done. Without that point, really, your apology doesn’t stand. You can’t just quickly apologize for your behavior unless you really understand what has caused the offense. And that takes a lot of time. And guess what? That’s what Yom Kippur is all about.

Do you know that Kol Nidre is the longest service in the year? Why? Because we’re doing that apology stuff to God. Takes a long time.

I was listening to the radio and I couldn’t believe, as I was thinking about apology and all these averahs these sins that have been all around us, people who have offended and not had any apology – there was a whole conversation about how to bring offenders back into this community around the “Me Too” movement. Tarana Burke who coined “Me too,” understood in this interview that she is going to take care of the victims. We still need to hear the stories of the victims, we’re still hearing new stories of the victims. But she said that our community and our society has to also work on what it is to reconcile to where we can bring together these broken realities in our world. She says it really is not going to go away, sexual violence, until we understand why the wrong-doers did what they did. And in addition, for us, to acknowledge that giving them an entry back into society through the backdoor – through podcasts, through books – that isn’t going to help either. Forgiveness without an apology is cheap. We have to figure out how they are going to come back and do real t’shuvah, real atonement, do restitution because she believes that the people who are part of the problem are the exact people who have to be part of the solution. I loved that.

Burke understood that we as a community must reckon with the realities of reconstituting some understanding of how we treat one another.

Lazare goes on to talk about the fact that not only can one apologize too soon, but we also have to understand the history of apology. It was actually after WWII that apologizing became a part of civilized society: not as a reflection of weakness, but actually seen as a strength, which I think is a wonderful thing. He also went on to say what happens when you have to take responsibility for something you didn’t do? That’s something we struggle with, isn’t it? He explains that it’s sort of like buying a house. You buy the house and you own the things that you love. But you also own the hot water heater that bursts the day after you sign the papers – you own that part of the house, too. He says we have to take responsibility. We feel very proud of being part of this country, but we also feel the shame of this country being built on the back of slaves. We have to own both parts.

I’m very proud to be part of this community and this congregation and I feel honored to be the Senior Rabbi. And yet over this year you’ve received two letters about previous sexual misconduct from a youth leader in our community. And I feel ashamed of that. And I feel responsible for that. I have to take all of it.

Abraham Joshua Heschel said about WWII that there were few who were guilty, but all were responsible. Few were guilty, all were responsible. I think that is very much what it means to be a part of this community and understand that apology is part of this wider world. In This American Life there was an amazing story – there was an apology that the victim actually tweeted – that was a master apology. It healed a wound that was deep. Dan Harmon who is a head television writer, was attracted to a young writer who was part of his team. He put her work first above all the other writers; he created a jealousy in the group and an uncomfortable situation. She kept telling him, “don’t show me favors – don’t do this.” And then he told her he loved her. She said you’re my boss; no. And then he decided to make her pay for his humiliation. He publicly humiliated her over and over again. Six years passed and Dan made a public apology. He said exactly what he did, word for word. He took responsibility. He said, “I had these feelings and I knew they were dangerous so I did what I coward does and didn’t deal with them. I made everyone else deal with them.” He said, “I didn’t respect women. Because I wouldn’t treat somebody like that if I did and I would never treat a man like that.” She, Megan Ganz is her name, heard it on this podcast and was touched and amazed. She felt that there was a reconciliation that she didn’t think was possible. She felt freed and liberated and said she didn’t realize, hearing from him – ironically, the very person she never would have asked – to tell her what happened was true; she needed that affirmation. She needed him to recognize that he had actually hurt the very core of what she loved about herself, which was her creativity. She told everyone to listen, and then Dan said something that I think was important. He said you know, I think the world’s going to be better because we (meaning men) won’t get away with it anymore, and I think that’s a good thing.

The idea that you can actually ask for an apology or forgiveness or give it, that we put somebody else’s concern and belief and hurt above our own, that is when we heal. There is the head of the Orthodox youth movement, David Bashevkin, and he wrote a book called Sin-a-gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought. He talks about a Hasidic group who understands that when we sin and ask for forgiveness and do the apology that we’re actually elevated to a higher status than just enjoying life in the perfect world. He said that the idea of coming to terms with our faults is the way we create a repaired world, of tikkun olam. He says that the people who show a complicated family history to their children and grandchildren, not only talking about the successes but also about the time you failed – the time you lost the job, the time you made the wrong decision – the time your family history isn’t so great along with when it is great actually creates a stronger next generation and a strong family. Personally, it’s the same. When you can talk to your family about the things you did wrong, about the losses and gains, the failures and successes, those are the ways we actually learn to be human. The Hasidic group says don’t be in duress. Don’t sit and try. Do the work of asking for forgiveness, of apologizing, because it makes the world stronger because of it.

We also are here to do the work. You can’t really do redemption or atonement without asking for forgiveness and an apology. I often hear people coming into sanctuaries every year saying, I don’t really like saying all those al chets – I haven’t done so many of them! I haven’t done this or that… and I think it’s so funny because I hope this year we lean into it. Instead of saying I don’t do this, let’s look at understanding it a bit differently.

One of my favorites from the previous machzor is confusing love with lust. If we keep that sin to the Harvey Weinstein, Cosby, or Louis c. k., then we’re really not doing the work we should. If lust fundamentally is power, which it is – having power over somebody else – and love is seeing eye to eye with another, sacrificing for another, listening to the hurt you caused even when it makes you feel uncomfortable – that’s love. I think sometimes we confuse the two. When we want to be right in an argument and win, that’s lust. That’s being powerful over love. I hear many people who have been married 50 years say that the best thing they ever learned in a marriage is that it’s better to be happy than right.

This Yom Kippur, let us identify with those three students on the train. Let’s find the time that we have to return to the scene and apologize because we haven’t treated somebody well or right. Let us return, just as I hope they would return. When we apologize and do the hard work of introspection, when we go to another person and show our remorse, when we build reconciliation, the world is healed. The world is that much stronger. If each one of us did that, think of what a beautiful community this would be. It would be one of strength, one where our souls would soar. Where our hearts would beat, where our hands would hold. That’s the community and world I want to create and I want to be a part of. G’mar tov.

Rosh HaShanah: Sanctuary Service

Sermon by Rabbi Jennifer Hartman

2019/5780

Failure is not an option.

This famous phrase is associated with Gene Kranz, the renowned NASA flight director for the aborted Apollo 13 space mission. It also became the tagline for the eponymous Hollywood movie . . . and it is purely Hollywood. Krantz never actually said this phrase.

In my opinion, the line should have been failure is always an option. In fact, when we look back on the greatest inventions, failure – and more importantly, the courage to fail – is what led to success.

Which is why it is so confounding that we tend to focus on the “either/or” of success and failure, rather than the both/and. In fact, who we are, and how we respond to the events of our lives, makes a much greater impact than the events themselves. Our first example of this is in God’s actions. In Torah, God has many human attributes: God loses God’s temper and questions God’s own judgement. God changes God’s mind and decides to take a different direction based on experience. Even God is not so headstrong as to be unable to learn from mistakes. We see this very clearly in the story of Noah’s ark. We read in Genesis that God brought a flood to the earth because “God saw how much human evil there was on earth and felt that the only way to remedy this was to destroy humanity and begin again with Noah.” After the flood, there seems to be a change in God’s opinion. The Torah reads: “I will not again curse the land because of humans, since the human heart is immature.”

This idea of an immature human heart intrigues the rabbis. They determine that it refers to our yetzer harah – our inclination to act only in our own self-interest without thinking of the bigger picture (as opposed to our yetzer hatov – our good inclination – which comes later). In the story of the flood, it is the yetzer harah that made humanity act dreadfully and anger God to the point of destruction. It was only after seeing the effect of the flood on the world that God took a minute to unpack what caused humanity to act with such baseless instincts. God began to try to better understand people and reflect on that hasty judgment in order to treat people with more patience moving forward. God, our commentators write, determined that Noah’s contemporaries were ruled only by aggression, viciousness, greed, and moral indifference.Therefore, God decided to give humanity the Torah with lessons of humility and honesty.

As the sages unpacked this view of humanity, they began to realize this was only half of the story. We are not all bad! This is where the yetzer hatov – our good inclination – comes into play. The yetzer hatov enters us when we come of age, around the time of our bar or bat mitzvah. The sages continue by teaching that as we grow and mature from adolescence to adulthood, we develop our ability to balance these two sides of ourselves.

While an interesting idea and explanation, this simplifies the concept to a degree that makes these two drives polar opposite rather than on a spectrum. As Professor Jeffery Spitzer explains, our yetzer hara is not a demonic force that pushes us to do evil, but rather a drive towards pleasure or property or security. It is a worldview that is just about us. It is the material force inside of us.

On the other side, the yetzer hatov is a worldview that holds us responsible for the other people in our lives. It is what allows us to feel empathy for another person, to want to reach out and help.It is the spiritual force within us.

Both of these forces, if left unchecked, have negative consequences. With our yetzer hara we act only in our own self-interest.With our yetzer hatov we act only in the interest of other people.When the two come into balance we do things that benefit ourselves and the community – like get married and raise families, start businesses that employ others, work for safe and friendly neighborhoods. This allows us to live in harmony with our inner selves.

A popular comedy that just began its fourth and final season, The Good Place, picks up on this very Jewish idea that each of us has good and evil inside of us. Spoiler alert! The show begins with Michael, a demon, conducting a radical experiment on a new way to torture human beings. He picks four people with questionable ethics, who would never have gotten along in life, and puts them into close community. When they “arrive” in his neighborhood, he tells them they have come to “the good place” – heaven – and lets them loose. His theory is that humans are self-centered and mean enough that they will spend eternity torturing one another.

Then enters the protagonist, Eleanor, who wants to become a better person. When Eleanor enters The Good Place she is told it is because of all the humanitarian work she did in life. She is then introduced to her alleged soulmate Chidi, a professor of ethics. During the first season Eleanor admits to Chidi that there was a mistake and she was not a humanitarian in life. But, she wants to learn how to keep her yetzer hara in check. She wants to balance it with her yetzer hatov! Chidi agrees to teach her ethics. In return, and unknowingly, Eleanor helps Chidi to keep his yetzer hatov in balance: you see, in life, Chidi was so concerned with making the ethical decision that it paralyzed him making him unable to make any decision at all. Eleanor’s self-centered experiences are exactly what Chidi needs to live life – even if he is already dead!

Recently at Temple, we heard an extreme example of what happens when our yetzer hara (our “selfish” side) is out of balance. Oshea Israel and Mary Johnson-Roy told us their story of betrayal and forgiveness. On February 12, 1993, Mary’s 20-year-old son was shot and killed by then 16-year-old Oshea during a fight outside of a bar. Oshea was sentenced to 25 years in prison for second degree murder. Twelve years into Oshea’s sentence, Mary sent a request to visit him in prison. At first Oshea refused, but eventually he changed his mind. The two met and talked for over two hours. Oshea admitted to the murder and Mary forgave him, fully and completely. She could not believe she was able to do this, but she said that as she did, she felt like a weight physically lifted from her. For Oshea, Mary’s forgiveness brought both changes and challenges to his life. He said, "Sometimes I still don't know how to take it, because I haven't totally forgiven myself yet. It's something that I'm learning from Mary. I won't say that I have learned yet, because it's still a process that I'm going through."

For Oshea, part of forgiving himself is allowing himself to make big changes to his life, and surround himself with people who will help him do this. As he was speaking here at Temple, Oshea talked about adders, subtractors, multipliers, and dividers. Adders are people who add to our lives while subtractors take away from our experiences. Multipliers, on the other hand, lift us up to a higher plane then we could have imagined for ourselves while dividers pull us down into deep holes.Oshea talked not only about the need to surround ourselves with multipliers and adders, but that each one of us, at different times, are all of these things to ourselves and to others.

We all find ourselves in difficult situations, big and small. And we all make mistakes. But that should not, and cannot, keep us from asking: Who are we? What role are we playing in the success or failure of our own life or the lives of others? What can we do next to move forward? How can we help our compassion win over our fear? Our kindness over our greed? This is the lesson of t’shuvah, of repentance, of cheshbon hanefesh, of examining our souls.Our goal is not to be perfect, but it is to be open enough to learn from our actions when we are out of balance.Our goal is to never stop trying to be the adders and multipliers in the world. And those years when we are more to one side or the other then we would like to be? Those are the years we tend to beat ourselves up the most. But, in reality, those are the years when we have the most opportunity for growth.

Rosh HaShanah is known in Jewish texts by many names including Yom HaZikaron - "The Day of Remembering” and Yom Hadin - "The Day of Judgment." We understand the reason for Yom Hadin, but why, the rabbis wondered, is Rosh HaShanah referred to as a day of remembering? The answer comes from a midrashic description of God sitting upon a throne, while books containing the deeds of all humanity are opened for review, and each person passes in front of God for evaluation of their deeds. While I am not sure that my theology is such that I believe in a God who sits on a throne examining all of our actions over the past year, I do like the idea of spending time remembering – and assessing – our own past conduct and contemplating our path forward.

This image helped me recently as I thought about a comment a student made. She felt that she apologized for wrongdoings as they occurred and therefore did not need a dedicated day of repentance. As I thought about her comment, I realized that we give the wrong impression if we think that these days of awe replace apologizing in the moment. Rather, they give us time to look back and reflect on the past year. Unpack times in which our inner selves were unbalanced. Go back and finish conversations we only started.Maybe even apologize again, with more thought and meaning this time, to people we hurt.

As I think about my student’s statement, I cannot help but think about how defensive we all become when confronted with our wrongdoings. When asked what made Oshea finally agree to see Mary, he said, “For years I didn’t even acknowledge what I’d done and would lay the blame on everyone else. I didn’t want to hold myself responsible for taking someone’s life over something so trivial and stupid. You blame everyone else because you don’t want to deal with the pain. Eventually I realized that to grow up and be able to call myself a man I had to look this lady in the eye and tell her what I had done. I needed to try and make amends.Whether she forgave me or not was not the point.”

It is truly all about the framing. Oshea could have viewed apologizing for his crime and all of the pain he caused as a weakness, as something only cowards do. Instead, he realized that this took courage and maturity. It was not easy, but it has allowed him to use the senseless act of crime to help others avoid his mistakes. Acknowledging, admitting, even accepting and embracing our flaws and imperfections is what will enable us to become the best versions of ourselves. It is our drive to be perfect that can paralyze us from action.

I wonder what would happen if we understood and internalized that we are ALL at different points of the same path. That we have years when we take more steps forward and other years when we take more steps back. That God is not perfect, therefore we should not and cannot expect ourselves to be perfect.Would this allow us to open our hearts and our souls to one another? Would this enable us to look another person in the eye and say “I am sorry” with meaning and conviction? Would facing ourselves with this level of chesed, of kindness, allow us to see the other with the same empathy?

Our machzor teaches that, “For sins against God, the day of atonement atones, but for sins from one human being to another, the day of atonement does not atone until we have made amends with each other.” This very important text leaves out one integral part of the scenario.We cannot embark on the work or the lessons of t’shuva until we learn to treat ourselves with kindness and compassion. Until we are able to admit and forgive our own wrongdoings. Then, and only then, will we be able to look kindly on each other. This is our challenge in the coming year, this is our path to move forward.

Rosh HaShanah: Youth-Led Creative Service

Sermon by Rabbi Tobias Moss

2019/5780

Un’taneh Tokef. Let us proclaim the sacred power of this day, awesome, full of dread.

Who by fire? Who by water? Who by slow decay? Who by moose?

Who by moose?! No, that wasn’t said out loud. That was in my own reading as I thought of what was my closest call, closest brush with death during the past year.

Who by moose?

I began this summer with a 1,700 mile drive from my home in New York City to my new one here in Minneapolis. Accompanied by two of my most adventurous friends, we took the scenic route, driving on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes. It was beautiful and I was full of excitement for this transition, for joining Temple Israel, for leaving the crowded Big Apple and coming to the Land of Lakes.

As we started to drive Superior’s northern shore, a new traffic sign was spotted popping up along the road: yellow signs with muscular antler-clad animals in mid-gallop. These weren’t like the slender deer signs I’ve known in suburban New Jersey. There were two words posted below the image: night danger. But sometimes you see a sign without understanding its significance. So we drove along after the sun had set.

I was behind the wheel when, out of the darkness, only some yards in front of the car,

I suddenly identified a cluster of skinny legs and hulking bodies. I was horrified and confused about why people would cross a highway at such a dangerous spot.

My instinctive reactions took over as I swerved out of the way. We pulled over and caught our breath. The three of us pieced the image together. We had just barely dodged two humongous black-furred moose. They were nearly invisible on the dark highway. As far as I’m aware, though one never knows for sure, that was my closest brush with death from the past year. Who by moose?

Now were I to try to further update Leonard Cohen’s “Who by Fire,” itself an update on Un’taneh Tokef, “Who by moose?” just wouldn’t cut it. It doesn’t sound elegant enough; it’s not the way I’d choose to go. But then again, one of the points of this prayer is that in real life we don’t know how, we don’t know where, we don’t know when we will go. However, at this awesome time of year we muster the collective courage to ask the question who by this, who by that?

At last year’s asking of “who by fire,” no one could have known the answers: which house would have a freak electrical fire and everyone wouldn’t make it out, that the Amazon would burn with unprecedented intensity; that in nearby Duluth, Adas Israel’s 118-year old synagogue

and eight Torah scrolls would go up in flames just weeks before this year’s High Holy Days.

And as for the coming year, we know that tragedy, or if we’re lucky, only adversity, will certainly befall us. So once again we ask: Who by this? Who by that? Come on God, come on Judaism, give us a roadmap for the year to come! We get none.

We hear no answers to those explicit questions of the poem. But we do hear an answer to unspoken questions. What shall we do in advance of such tragedies? What shall we do after they come to pass? We don’t get a roadmap, but we do get direction.

וּתְשׁוּבָה וּתְפִלָּה וּצְדָקָה מַעֲבִירִין אֶת רעַ הַגְּזֵרָה

T’shuvah, t’filah, and tzedakah will temper the severity of the decree.

Repentance, prayer, and righteous giving will ease the hardship of what’s to come.

It is not a detailed roadmap, but it is a compass, a way to navigate during these ten days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and in the year to come. Three stars to follow:

T’shuvah – repentance

T’filah – prayer

Tzedakkah – righteous giving

However, just learning a bit of orienteering doesn’t mean it is easy to get where you want to go. They don’t erase the hardships of life. They temper them, reshape them, help us to make meaning, move beyond the bad to experience more of the good.

I’ve learned about these three guiding principles from two of the most Minnesotan things I’ve done during my first few months here.

The challenge to “temper the hardship of the decree” was the central theme that I encountered during my obligatory first pilgrimage to the Guthrie Theater—you see Minneapolis caught my eye not just for its proximity to lakes and moose, but also the acclaimed theater scene.

At the Guthrie, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Lynn Nottage debuted her newest play about a truck stop sandwich shop, Floyd’s. The whole play takes place in the sandwich shop kitchen where ex-convicts are striving for two goals with equal fervor: repentance and the perfectsandwich.

Three young cooks were recently released from jail, but are struggling with the stigma they receive from the outside world and their own persisting guilt. They are easily set off when someone brings up their past, and they have great concern they’ll fall into bad habits. These three look up to a wiser and older cook, Montrellous, who seems to have moved beyond his own troubled past.

“Look here, being incarcerated took a little something from all of us. Cuz you left prison don’t mean you outta prison. But, remember everything we do here is to escape that mentality. This kitchen, these ingredients, these are our tools. We have what we need.”

This is the Jewish belief. We have what we need. T’shuvah is possible.

My teacherRabbi Larry Hoffman notes that one biblical description of sin is that it is a burden that weighs us down. God nosei avon, lifts up, that burden. If God removes the burden on a person, then so must society practice forgiveness, then so must we each practice forgiveness with ourselves.

T’shuvah is largely about dealing with our past. This season’s second guiding principle,T’filah, prayer—especially petitional prayer—is how we express our hopeful reaching out towards our future. We allow our souls to express our deepest desires. We join together with our people to do the same.

Throughout the play, the cooks come together for their own sort of communal ritual as they prepare simple sandwiches. They dream. They daydream. They dream out loud about discovering the ultimatesandwich!

“Cubano sandwich, with sour pickles, jalapeno aioli and . . . and sweet onions!”

“Grilled blue cheese with spinach, habaneros and . . . candied apples.”

“Maine lobster, potato roll gently toasted and buttered with roasted garlic, paprika and cracked pepper, mayo, caramelized fennel, and a sprinkle of . . . of . . . dill,”

(I knew I’d have to do this sermon on Rosh HaShanah, because this would be too painful to hear on Yom Kippur.)

Rafael asks: “Can the perfect sandwich be made?”

Letitia asks: “When we get there, will we know?”

And again, the wisest among them, Montrellous, responds: “We can only strive for the harmony of ingredients. That’s all.”

Here in synagogue, we don’t usually dream together of the perfect sandwich.

We dream of a world perfected.

We pray for peace.

We pray for community.

We pray for healing.

Our prayers don’t get answered in a direct or explicit fashion, but as Montrellous suggests, we nonetheless strive towards these ideals in our daily lives, though we do not know whether we’ll ever achieve our ultimate aims.

As 20th century Reform Rabbi Rabbi Ferdinand Isserman eloquently puts it: “Prayer cannot mend a broken bridge, rebuild a ruined city, or bring water to parched fields. Prayer can mend a broken heart, lift up a discouraged soul, and strengthen a weakened will.”

To elucidate our third guiding principle, tzedakah, righteous giving, I’d like to share a lesson from an unexpected place, from my most Minnesotan day here: the State Fair! We don’t have that sort of thing where I come from.

The fair’s nickname is the Great Minnesota Get Together. It seems to me that this has at least two meanings, the first being all the people that get together, and the second being all the subjects, themes, and attractions that get brought together. You can learn about the latest in organic lawn care or you can eat a deep fried waffle-encrusted breakfast sandwich on a stick—I don’t think that’s the perfect sandwich. You can walk through an art gallery made of corn kernels, or, as I did, you can spend half an afternoon learning how honey is made.

Rabbeinu Bachya, an 11th century Rabbi, writes in his book Chovot HaLevavot, Duties of the Heart, that one has the internal duty to see the world not just as it plainly seems to be, but to seek lessons from nature. We should observe and contemplate the natural world, and deduce Divine wisdom from this practice. And so in the middle of the State Fair I asked myself, and the beekeeper, what I could learn from the bees.

There are many other types of bees. There’s the bumble bee, carpenter bee, mason bee, leafcutter bee, and sweat bee, not to mention wasps, hornets, and other, meaner varieties.

When it comes to honey production, these other bee species are stingy. They only produce enough to survive day by day. When winter comes, the entire hive dies, every worker bee dies, save for the queen who hibernates alone for the winter, and then starts the hive from scratch in the spring.

But the honeybee does things differently. Even once they’ve made enough honey to keep the hive alive, they just keep going. They can end up making three, four, five times as much honey as they’ll ever consume.

Thanks to this generous spirit, if you will, when winter comes, even here in Minnesota, the hive survives along with queen. Thanks to this generous spirit, humans can enjoy from the honey surplus, without harming the health of the hive.

Likewise, for us, tzedakah helps our community survive the winter, the weak along with the powerful. Tzedakah is also how we share the sweetness of life.

Tzedakah is too often translated as charity, which limits the idea to only material giving. While our tradition does challenge us to do with less and give more, it also invites us to recognize the other bounties we have to share as well. Here the Bible’s Book of Proverbs teaches another lesson from the honey bee.

צוּף־דְּבַשׁ אִמְרֵי־נֹעַם מָתוֹק לַנֶּפֶשׁ וּמַרְפֵּא לָעָצֶם׃

Pleasant words are an overflowing honeycomb

Sweet to the soul, healing for the bones.

As you eat your High Holy Day honey, don’t just revel in the sweetness of the moment, but also let the honey serve as a guide. As you enjoy the surplus that the bees made, what surplus do you have that you can offer as tzedakah? What can you do to help the hive survive the winter, the weak along with the powerful? How you can help the community not only survive, but also taste life’s sweetness during these ten days and throughout the coming year?

One day we will all reach our end. Some of us by fire, some by water, some by slow decay, but hopefully none of us by moose, since we all now know what those “night danger” signs mean.

Jewish tradition acknowledges this human reality, our human frailty. Rather than let it halt us in our tracks, we do not experience our mortality as a dead end, that there is nowhere left to go because of it.

Un’taneh Tokef concludes:

Our origin is from dust

And our end is to dust.

But God,

You are beyond description.

Your holy name suits You

And You suit your Name,

And somehow we are named After You.

May Adonai Eloheinu, the Eternal Source of Strength, give strength to Am Yisrael the People Israel and all humanity, as we navigate the New Year to come. We have no roadmap, but we do have these three stars to follow. T’shuvah, T’filah, Tzedakah. Repentance, Prayer, and Righteous Giving.

Shanah Tovah.

Rosh HaShanah: Sanctuary Service

Sermon by Rabbi Sim Glaser

2019/5780

A couple of weeks ago Barb and I saw a wonderful film about the origins and history of Fiddler on the Roof. Among the extraordinary facts about one of the world’s most famous musicals is that since it first premiered in September of 1964, Fiddler on the Roof has played on a stage somewhere in the world every single day, including Vienna, Mexico City, Iceland, and even Japan!

My favorite moment from the documentary was when they showed clips from the Tokyo production of Fiddler. The scene where Golde brings Tevye his Shabbat sushi is just precious… and the accompanying musical number:

This fish - it’s not - gefilte!

Gefilte - this fish it - is not!

Ok, I made that up . . . But there really was a Tokyo production and the lyricist, Sheldon Harnick, attended a performance, and after the show he was asked by some of the cast members: Do they understand this show in America? It is so Japanese! And then there’s the delightful snippet of the Temptations singing “If I Were a Rich Man.”And a recent production of the play by Harlem schoolchildren in New York.

Fiddler on the Roof may be a musical about the precarious nature of Jewish life in the Eastern European shtetl, but the message of the documentary was that Fiddler belongs to the world. Turns out that being uprooted from one’s homeland and forced to forge a new existence in a distant unknown land is not limited to the Jewish national experience. Nor is the celebration of life, or the desire to see one’s children find happiness in their relationships, or the importance of keeping alive one’s traditions! Fiddler endures because nearly every culture on Earth has gone through upheaval, including our own current American 21st century experience.

Throughout history, the Jew has had an uncanny way of capturing both the admiration and the loathing of host countries. Rabbi Zimmerman brought back from her Eastern Europe trip some popular Polish talismans, or good luck charms. One of them – this one is of the little Yiddl with a fiddle clutching a 1 grosz coin – a Polish penny. This is not a relic from the 2nd World War era. You can buy this on a Warsaw street corner today!

Perhaps the fascination with the all-at-once precarious yet successful Jew is in how we represent so many elements of human nature. As someone once said: “The Jews are like everybody else, only more so!” The urge to prosper and be secure and strong versus feeling the abject fear of rootlessness and vulnerability. Perhaps because we celebrate life so intensely and mourn death so deeply. Perhaps because we have suffered so immensely, but remain so steadfastly determined to choose life, and to battle suffering and oppression when we witness it anywhere to anyone. Because we sing about the sunrise and the sunset and swiftly flying years – One season following another, laden with happiness and tears…

Or maybe it is because we are so overtly familiar to people. We wind up being the mirrors of self-love and self-hate. And strangely enough, at .17% of the world’s population, our welfare winds up being the barometer of the health of any given society in which we dwell.

New York Times journalist Bari Weiss, who became Bat Mitzvah at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh 20 years ago, writes about how when a society is in decline, anti-Semitism takes root. Societies in which hatred in general – and anti-Semitism in particular – thrives are societies that are dead or dying. Why is that? Because anti-Semitism is the ultimate conspiracy theory – so it thrives in a society that has replaced truth with lies. Anti-Semitism, she writes, is an intellectual disease, a thought virus – as long as the body is healthy the virus doesn’t cause trouble. But when the body is ill the virus breaks out!

This we should consider relevant, because our own American social immune system is in a weakened state. When we witness these sporadic but increasing incidents of hatred, we know that our nation is in trouble. We have witnessed Charlottesville in our own time. Pittsburgh. And in today’s political climate, not very far from our front doors, elected officials can make anti-Semitic statements and survive politically!For some of us this is a new phenomenon, for others it is 2,000 + years old.

The synagogue fire in Duluth turned out not to be a hate crime, but there was a collective holding of breath for the two days until that information was made public, and I don’t think it was the Jewish community’s fear alone that made it front page news. I think the people of this state were determinedly interested in knowing where we are headed! When a synagogue goes up in flames, the world takes note.

The Tevye character in the most recent production of Fiddler enters the stage wearing a contemporary red parka as though he has just gotten off a raft crossing the Mediterranean. The characters’ accents are minimal as though to suggest: This is everybody’s story!

The Fiddler on the Roof documentary concludes with a striking series of photographs of refugees around the world in search of a new and secure home juxtaposed with the closing scenes of the Jews leaving Anatevka, followed by classic pictures of Jews being loaded into German boxcars and the liquidation of the ghettos.

These are stark reminders that although we may have, as a people, endured some of the worst suffering in human history, an increase in hate and a wanton disregard for the plight of refugees are harbingers of societies in decline.

So it did not seem much of a stretch for the leadership of Temple Israel Minneapolis to take in an undocumented Nigerian man and provide sanctuary for him as he sought to evade ICE agents determined to deport him. Felix lived with us on the third floor of this building for six weeks before he endeavored to return to his workplace so as to have the health care required by his ailing wife. No sooner did this loyal employee arrive on the job than he was picked up by ICE; he now sits in a detention center in Elk River awaiting an uncertain future.

And it doesn’t seem such a stretch to learn that one young member of our congregation gained knowledge of a family separated, with mother and daughter living here, while their 7-year-old son remains caged in a detention center on our southern border, and came to us asking for assistance. We arranged to have him basically ransomed, released and flown up here to join his family.

And it doesn’t seem such a stretch for this holy place to be assisting a family from Central America seeking a better life for their children in finding a place to sleep at night.

I know it may appear to many Americans that we are a more secure nation by breaking up migrant families, throwing children into detention camps, and deporting long-time residents who are richly contributing to our society. And I know there are those who believe that teaching each other to fear the foreigner – and each other – is good for the health and welfare of this country. I’m here to tell you, and I am the one with the microphone, that it is not! It is that same virus eating away at the American body. And nobody knows the consequences of that societal malady as intimately as the Jewish people do.

Sadly, I heard from members of this congregation after Pittsburgh that they were scared to come into our building. On the other hand, there were close to 2,000 people of many faiths and backgrounds who assembled here in defiance of hatred following that tragedy.

I believe people see themselves defined in the pages of our Jewish story. They feel the precarious nature of being human saw themselves in the telling of our personal tragedy. For at least a couple of days, everybody in town was fiddling on the roof.

Another interesting piece of Fiddler trivia, about which I was previously unaware, is that the original score contained an upbeat song toward its conclusion called “The Messiah Will Come.”

There is an old Broadway tradition known as the 11 o’clock song which they place a show-stopper number that wakes up the sleepy theater goers to keep their attention through the end of the show (much as a rabbi might do at this very moment in his sermon!).

In Fiddler the song you’ve never heard was called When Messiah Comes, and it goes something like this:

When Messiah comes he will say to us

I apologize that I took so long,

But I had a little trouble finding you,

Over here a few and over there a few

You were hard to reunite

But everything is going to be all right

Up in heaven there, how I wrung my hands

When they exiled you from the promised land

Into Babylon you went like castaways

On the first of many, many moving days.

What a day and what a blow!

How terrible I felt you’ll never know!

When Messiah comes he will say to us:

Don’t you think I know what a time you had?

Now I’m here you’ll see how quickly things improve, and

You won’t have to move unless you want to move

You shall never more take flight,

Yes, everything is going to be alright!

The song never made it into the show. The familiar story of Tevye and his family ends on a tragic note of being forced out of their home in search of a new and more secure future. Fiddler is one of the few musicals that doesn’t end on a happy note.

This is the universal message of the Jewish story that people of all faiths know in the deepest recesses of their hearts – We do not live in a Messianic world.We are still waiting for it! Working for it! And if we give into hatred and fear of the other, if we allow that virus to invade the body of humanity, then indeed, the whole world will know what it means to leave Anatevka in search of a new home…

On Rosh HaShanah, the birthday of the world, may we come closer to one another, and in doing so may we recognize all that the people of the world hold in common, far more than what separates us. The love of children, the deep devotion to long-standing traditions, a sense of humor, the fear of homelessness, a love of music, a will to live in freedom, and a desire for life! - L’chaim!

Erev Rosh HaShanah: Sanctuary Service

Sermon by Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman

2019/5780

Just this past month, a number of us from Temple went to Eastern Europe. We traveled through the places that our ancestors once lived and where so many died in the Holocaust. We went to Terezin, we went to Auschwitz and Birkenau. We went to the Jewish quarters of Prague and Budapest, of Warsaw and Krakow, of Berlin.